Porfirio Díaz Part 2: Progress for the Few

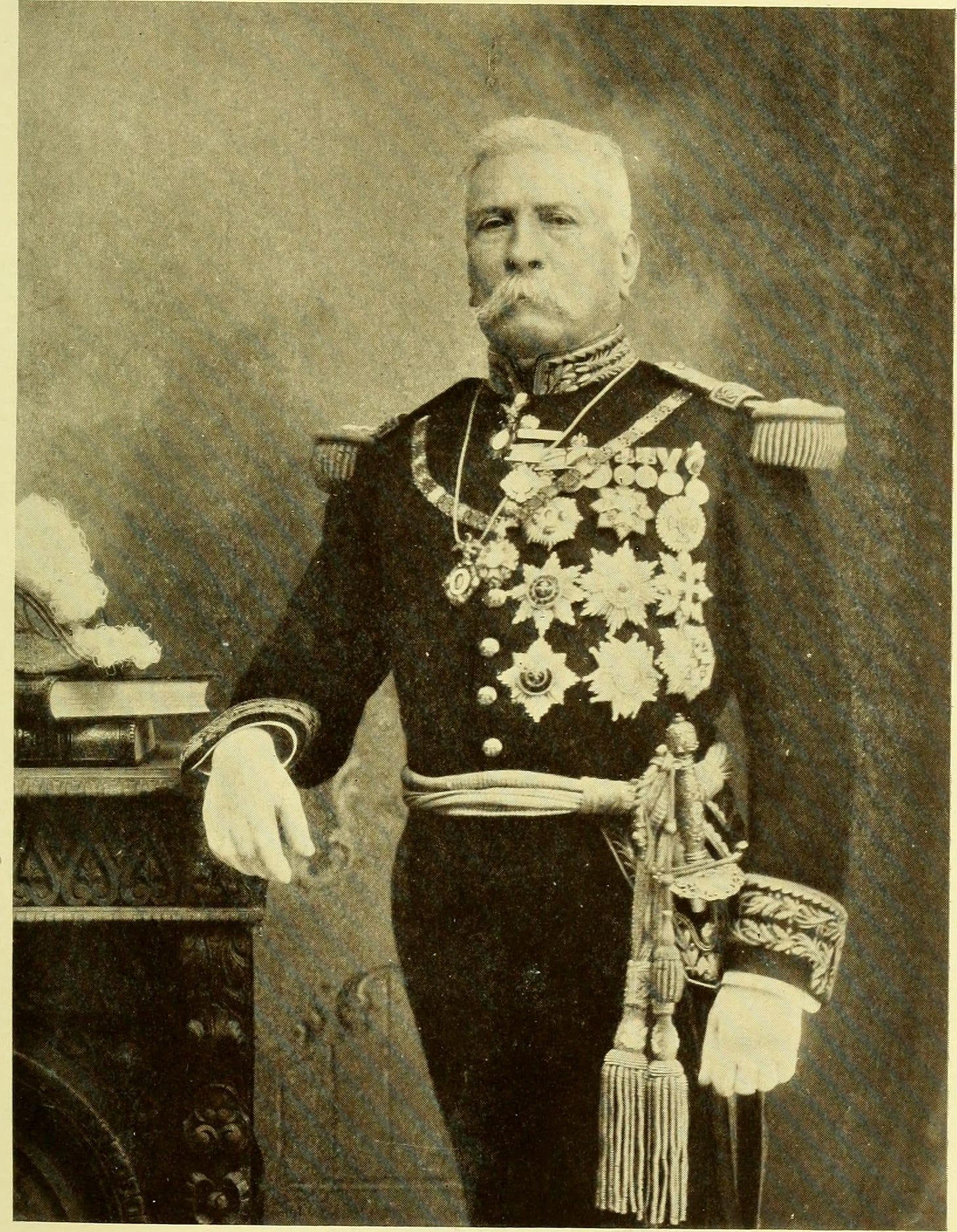

Porfirio Díaz, once hailed as a liberal reformer who ended Mexico's era of foreign intervention, would come to embody the very authoritarianism he once opposed.

From the end of his first presidential term in 1880, to his death in 1915 , Díaz’s trajectory reveals a paradoxical legacy of order and oppression, development and disenfranchisement.

Part one of this series ended as Díaz, a decorated general of the Reform War and the French Intervention, stepped aside as President in 1880, handing over power to his ally, Manual González. But this respite was short-lived.

González’s administration was spoiled in corruption and unpopular economic reforms, paving the way for Díaz’s return in 1884. By then, it was clear that Díaz’s commitment to democratic rotation had faded. He amended the constitution to allow his indefinite re-election - a decision that would shape Mexico for decades to come.

Díaz’s second presidency started the era know as the Porfiriato, characterised by fast paced modernisation, foreign investment, and relative political stability.

Railroads stretched across the country, linking far away regions and facilitating trade. Foreign wealth, particularly from the United Sates and Great Britain, flooded into mines, oil and agriculture. Cities modernised, lights lit up Mexico City and industries boomed.

But the economic miracle had its victims. Land reform was reversed, commercial land was exploited and sold to the rich or to foreign investors. Indigenous communities were displaced. Peasants and labourers faced rough working conditions with little alternative, as Díaz suppressed unions and workers strikes with military force.

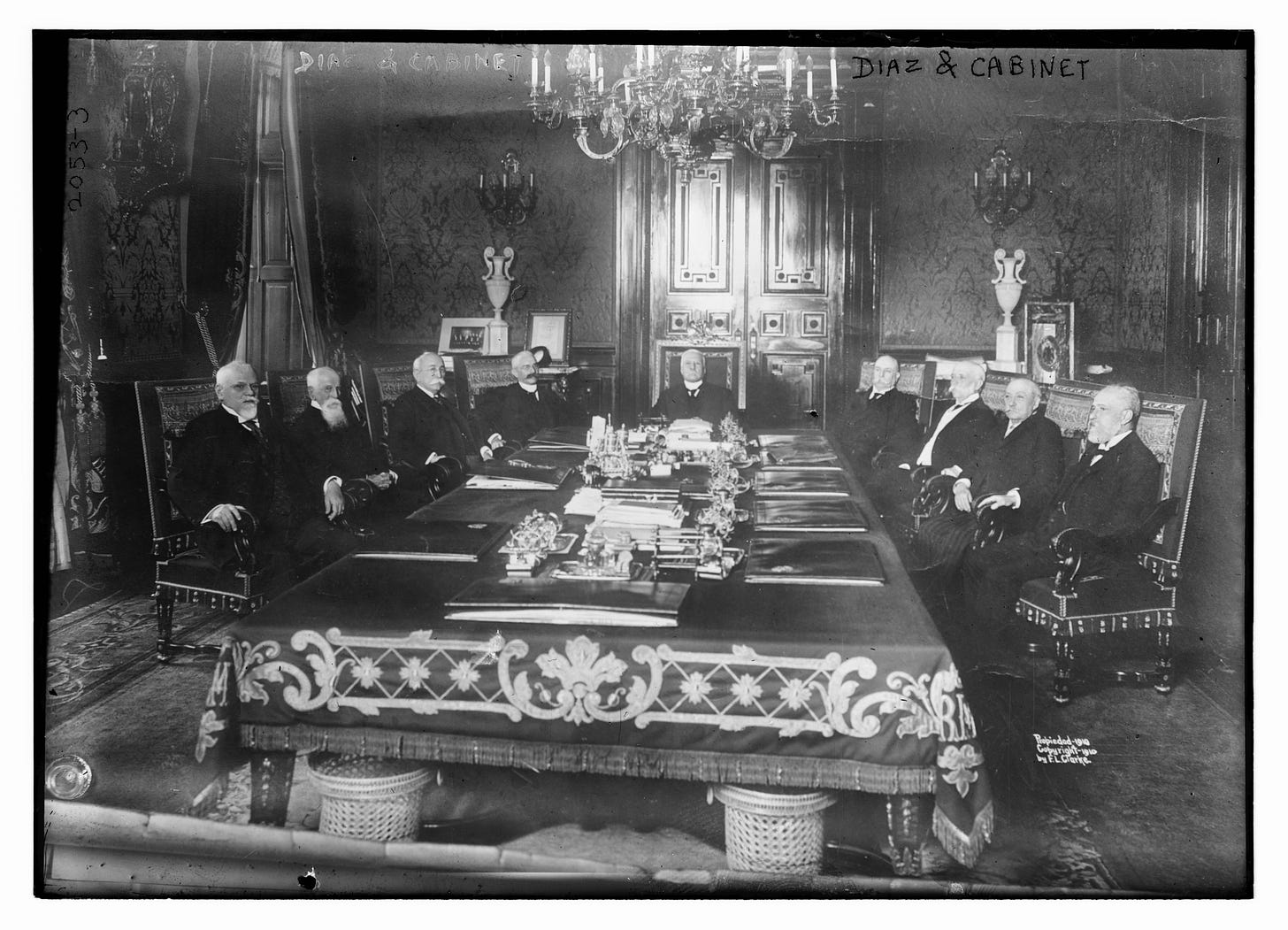

Díaz maintained strong control through his political machine. State governors owed their positions to him, the press were muzzled, and elections were rigged, but maintained the facade that democracy was in action. Beneath the illusion of order, resentment was bubbling.

As the 20th century progressed, cracks in the Porfirian system began to show. Economic divisions grew wider. Intellectuals like the científicos - Díaz’s technocratic advisors - adopted the idea of Social Darwinism in order to justify elite rule, alienating the broader public of Mexico.

In 1908, in a rare interview with American journalist James Creelman, Díaz suggested that he would not seek re-election in 1910. This idea emboldened political opposition, including Francisco I. Madero, a wealthy landowner turned democratic reformer who founded the Anti-Reelection Party.

Díaz would once again go back on his word. In 1910, at the age of 80, he ran for re-election - and claimed victory whilst facing accusation of fraud. Madero called for revolution, sparking uprisings across Mexico.

By May 1911, revolutionary forces, led by Madero, Emiliano Zapata, and Pascual Orozco, had gained the upper hand. Díaz resigned and he immediately boarded a ship destined for France, declaring, “Madero has unleashed a tiger, let us see if he can control it.”

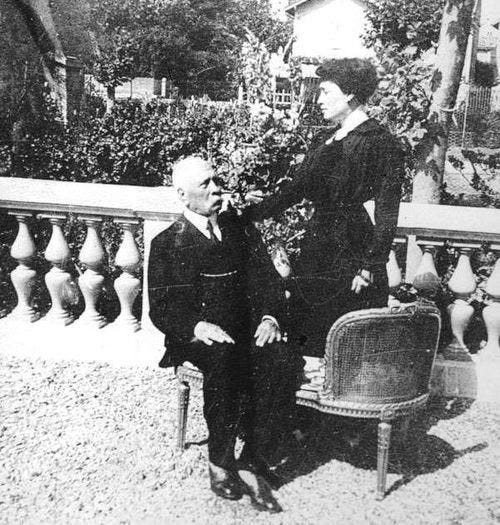

He would never return to Mexico. In exile in Paris, Díaz remained politically detached but not forgotten. He lived quietly with his second wife, Carmen Romero Rubio, and maintained connections with loyalists and family. He watched from afar as Mexico descended into chaos - a revolutionary period of struggle that would outlive him.

Porfirio Díaz died on July 2, 1915, in Paris. He was buried in Montparnasse Cemetery, far from the land he once ruled with an iron first in a velvet glove.

Díaz’s legacy remains somewhat undecided. To some, he was a visionary who brought Mexico into the modern world. To others, a dictator who betrayed democratic rules and enforced inequality.

A century later, the ghost of Porfirio Díaz still haunts Mexico’s memory - proof that even progress, when rooted in exploitation, can only last for so long.

Sources:

The Mexican Revolution - Alan Knight

Mexico: Biography of Power - Enrique Krauze

Disorder and Progress: Bandits, Police, and Mexican Development - Paul Vanderwood