Mao Zedong Part 1: The Long March to Power

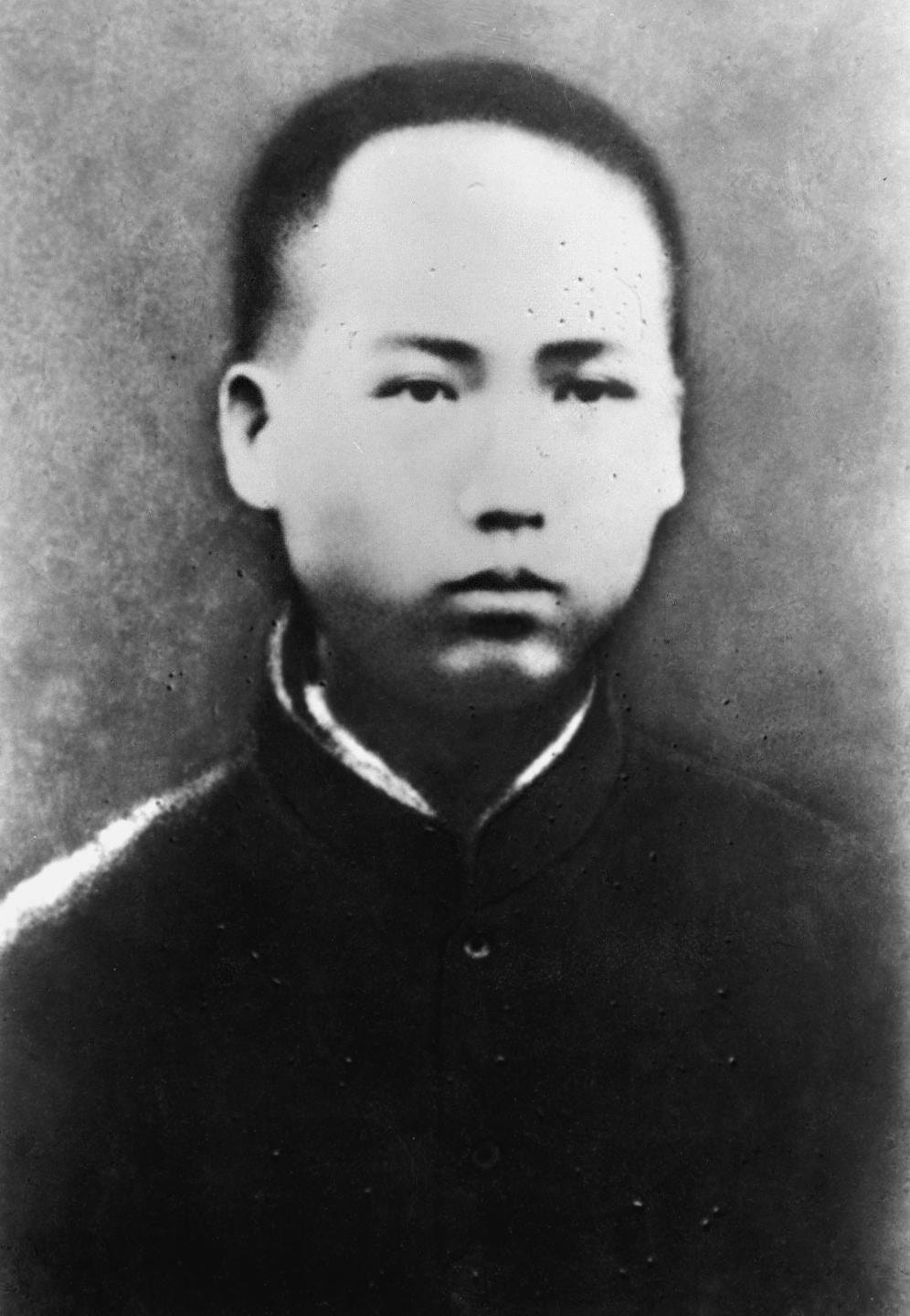

In the hush of a winter night on December 26, 1893, nestled deep within the rugged hills of the Hunan Province, a boy was born to a peasant-turned-landowner. That boys name was Mao Zedong.

Few could have foreseen that this child, with a head of black hair and storm in his gaze, would one day rise to bend the spine of a fractured nation - and command a revolution with the fire of myth.

Mao was no quiet peasant son. He rebelled early, first against the rigid Confucian classics his father imposed upon him, and later against the crumbling Qing Empire. By the time the 1911 revolution rocked China and sent the last emperor tumbling from the Dragon Throne, young Mao was already steeped in radical literature and hungry for transformation. He joined a local militia and watched from the margins as power slipped from dynasty to republic, from emperor to warlords.

In the newly founded Republic of China, chaos reigned - but Mao thrived in chaos. He wandered through the intellectual cause of the New Culture Movement, devouring Western philosophy, Marxist theory, and Chinese history with equal fury. The spark of revolution caught fire in his soul not in Moscow or Paris, but in the library of Peking University, where he worked as a humble assistant. There, Marx became gospel. Lenin, the prophet. Mao would be the sword.

In 1921, in the smoke-thick air of an underground meeting in a Shanghai shophouse, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) was born. Mao joined the party one year later, becoming one of a handful of delegates. But unlike his urban comrades, who clung to factory floors and Bolshevik blueprints, Mao turned to the hills, the villages, and the peasants.

“They are the sea,” “We are the fish.” he once wrote.

It was a revolutionary idea: China’s uprising would not be driven by the urban working class of Marx’s Europe - but by the barefoot, rice-growing peasants of its vast countryside. The elites dismissed it as foolishness. Mao stood firm.

The uneasy alliance between the Communist Party and the Nationalist Kuomintang Party cracked wide open in 1927 with the Shanghai Massacre - a brutal purge that saw thousands of leftists butchered by their supposed nationalist allies. Mao survived. Many did not.

Fleeing into the mountainous jungles of Jiangxi, Mao began his greatest experiment: the Jiangxi Soviet. There, amidst starvation, struggle, and ceaseless attack, Mao refined his theories of guerrilla warfare and political indoctrination. Land reform was enforced by bullet and shovel. Authority flowed from the barrel of a gun. Revolution, he declared, was not tea in a scholar’s study - it was fire and movement, sacrifice and fear.

The Nationalists were determined to crush the communist strongholds. Wave after wave of brutal military campaigns battered the Red forces. By 1934, with destruction looming, Mao and his beleaguered troops began a retreat so grand in scale and endurance, it would pass into legend: The Long March.

Over 6,000 miles of bitter terrain, across frozen rivers, snow-capped peaks, and sun-scorched plains, Mao led the broken fragments of his army northward. Of the nearly 100,000 who began the trek, barely a tenth survived. Yet by the time they reached Yan’an in 1935, Mao had done what few others could - he had seized the soul of the party.

Mao outmanoeuvred rivals and emerged as the undisputed leader of the Chinese Communist movement. His vision - both messianic and merciless - would now chart the course of revolution.

In Ya’an, Mao built a new base, a new myth. There, he wrote, lectured, planned. He became not just a man of ideology, but a master of political theatre - recasting himself as the Shepard of the people, the philosopher - warrior destined to reclaim China’s destiny from both warlords and imperialists.

By 1937, the ground beneath all of China shook. Japan’s imperial legions swept through the north, unleashing fire - and igniting a Second Sino-Japanese War. As bombs fell and civilians screamed, Mao’s Communist and Chiang’s Nationalists were forced into a desperate Second United Front, their uneasy truce forged in the crucible of national survival.

Yet even then, Mao’s gaze was fixed beyond war and towards the postwar reckoning. He welcomed the truce, but not the peace. For time. For Strength. For eventual, inevitable supremacy.

Thus, by 1937, Mao Zedong stood on the brink - not yet the omnipresent Chairman, but a revolutionary forged in hunger, betrayal, and flight. He had survived the purges, the massacres, the march of death. He had seen friends die, enemies rise, and empires crumble. The man who was once a peasant’s son from Shaoshan was now a dragon waiting in Yan’an, biding time as the fires of foreign invasion engulfed China.

The world would come to know him as a tyrant, visionary, liberator, and destroyer.

But in the blood-soaked year of 1937, Mao was not yet myth.

He had momentum.

He was waiting.

And the world had no idea what was coming next..

Sources:

The Search for Modern China - Jonathan D. Spence

China: A New History - John King Fairbank & Merle Goldman

Mao: A Life - Philip Short

Mao: A Biography - Ross Terrill

Mao’s China and After: A History of the Peoples Republic - Maurice Meisner

Great piece Reece!